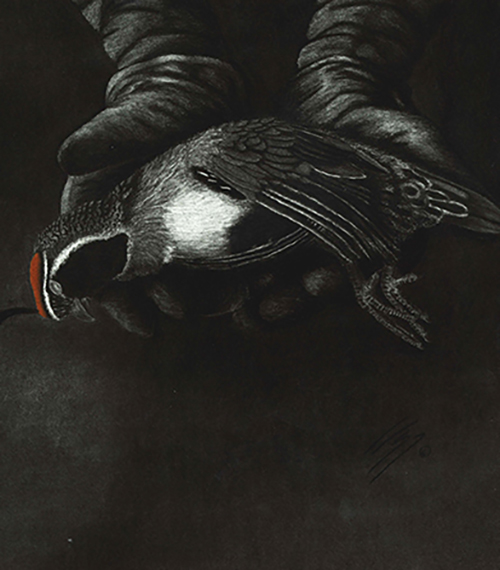

Story by Tom Reed Illustrations by Tanner Swank

Among mankind’s oddest penchants is the propensity to collect. My grandmother, a large, kind woman named Agnes, collected Hummel figurines, ridiculous cherub-cheeked characters in porcelain that one had to dust off every week. Who, I wondered, then and now, would want to have a bunch of that litter in the house? They made me pine for a hammer. Others among us accumulate dogs, old toys, classic cars, bottle caps, antique furniture, Winchester long rifles. You name it, we humans hoard it.

I wonder when this started. Surely our hunter-gatherer forefathers collected nothing not having to do with mere survival, but perhaps not. Consider the petroglyphs of La Ferrassie, which one might think of as reservoirs of story. Maybe they, like me and my hunting pals, were sitting around one evening enjoying a post-hunt repast and telling stories when one said to the other: “Hey bud, you better write that down.” Those Neanderthals of southwestern France perhaps collected adventures.

Some years ago, I realized I was close to gathering the rare experience of taking at least one of all the species of quail that inhabit our lower forty-eight. There are six of them. It was the third quail that started the whole bit. Maybe the fourth. I wasn’t really trying at first, but onceI was at three or four it seemed like a pretty easy jaunt over to five or six. The first three were a matter of proximity, as most of our upland birds are for most anybody. For me, it was Gambel’s, Mearns’ and then bobwhite.

Bobwhite

It seems odd to admit that I have the least amount of time hunting bobwhite than any of the quail, easily the most ubiquitous and well-known quail. I’ve just never lived particularly close to its territory. Far from my Rocky Mountain roots, my story with the bob is more vicarious than actual. My life-long mentor and best friend is a man my father’s age who introduced me to horseback sage grouse hunting in a high Colorado valley decades ago. He had also done a stint as a game warden in a tiny town in the San Juan Mountains and it was here that he met a passel of big ranch Texans who cooled off in the high country during the heat of the Texas bake before air conditioning was universal. One thing led to another and Jim, being a born-again bachelor, ended up invited on a Lone Star quail hunt hosted by a renowned Fort Worth dentist who ran Llewellin setters by the pack.

By the time I had met Jim, I had taken two species of quail as a college student in the desert Southwest, but Jim’s tales of bobwhite quail and those generous Texas hosts went long into the night, fueled by a good bourbon beside a fireplace.

Accounts of plucking quail by the bushel basket after a long day’s hunt, following the bird dogs on ranch roads in a convertible Cadillac with a man named Mule Stover at the wheel, going back south as the Colorado winters closed in year after year. Jim ended up with not only an anthology of bobwhite tales over those years, but also a fine L.C. Smith 20 and at least two setter pups courtesy of that generous dentist. Those stories made the bobwhite a want-to for me, but the problem was I was a poor newspaper editor in a frozen high-country town with hardly enough gas money to get through the week. They’d have to wait.

Then one late November day found me in Willa Cather country. By this time, I had moved to Cheyenne, Wyoming, which is like Nebraska without the pheasants, and I had made a new hunting buddy who ran a sweet golden retriever. We were on a quest and it was not quail, but those gaudy Chinese ditch parrots that induce the contradictory emotions of love and revenge.

In the days before CRP really took off and before GPS systems and cell phones, finding pheasant hunting in west-central Nebraska was something of a chore, but late one afternoon, we stumbled upon a block of public land that was a mix of cattails, Russian olive trees and shortgrass prairie. A mean wind was coming out of the west, but we turned Pat’s golden and my Splab (half Lab, half Springer) out into it anyway. It was the kind of wind that instantly brought tears and snot, but off we went.

Upland hunting is a walker’s game and you better love putting one foot in front of the other if you are chasing wild rooster pheasants in a thin country. Hours later, the sun just barely a glimmer on the horizon and fingers frozen bent, we made our way back to the truck and through a tree row. We could barely see the pickup off in the distance when the Splab got birdy and up went two little birds. I was expecting a cackling rooster pheasant, not a blur of fast-moving bird one third the size, but somehow I recognized quail, swung the shotgun and made a double.

.jpg.aspx)

It was a pair of bobwhite quail. We stumbled back to the pickup completely birdless, except for those two beautiful little quail. I recount this with some measure of guilt for they were like Cather’s pioneers on the far rim of the known world, just trying to get along and I stumbled in and ended their dreams. Such are the conflicts that plague a hunter’s heart as he kills what wants only to live. Those were and still are the only bobwhites I’ve ever taken.

Gambel's

Years earlier, before I had the mutt hunting dog, I spent my college years staggering around in the cholla and mesquite country of Arizona walking up Gambel’s quail, which might beat a rooster pheasant in a flat-out foot race. I was lucky enough to take many and add variety to a college pizza diet and I still occasionally go back and spend a few weeks there long enough to thaw out from a northern winter.

When I chase Gambel’s in this hard country, smelling winter rain on creosote flats, listening to the “Woo-Hee-Who-Woo-Hee-Who” of the sentinel bird in the covey, I am 19 again, wearing blue jeans and a t-shirt and some cheap vest I bought at Kmart, throwing an old clunker gun four times my age to my shoulder and drinking beer around the campfire at night as if a second Prohibition was just waiting for the president’s signature.

Mearns'

I hunt Gambel’s for sentiment, but I hunt Mearns’ because I’m a setter man now and have been ever since the day that good old mixed-breed Splab passed on. Mearns’ are a bird of a niche—the Emory oak grasslands, and because they are so specialized, and hold so tightly for a pointing dog, it’s a wonder they are not on the brink of extinction. But somehow they seem to self-regulate and nonresidents like me self-regulate too when word gets out that the rains have been kind and all appearances are a good season is in the offing. When the rains have been unkind and absent and the forecast is appearing poor, somehow word gets out on that too and fewer hunters make the trek to the great Southwest.

I started hunting Mearns’ in my college years when I was hunting Coues deer to supplement the food-in-a-cardboard-box-menu with a little acorn-finished venison. I almost stepped on a colorful clown male while packing around a bolt .270. I came back to that spot with my mutt and a shotgun and killed a few.

Mearns’ like the same cover year after year and I found that same covey again in the mid-1990s when I was on my own born-again bachelor trip. I bounced my old Dodge diesel into the backcountry, threw a bag out on the ground, curled up next to my young hard-charging setter and listened on AM radio to the Cowboys defeat the Steelers in a Super Bowl that was being played in the stadium of my alma mater just a few mountain ranges to the east.

The next morning, I bounced the Dodge out to another cover I knew, a place with amazing pink granite rock formations that rose above the steppe as picturesque as anything ever published in the famed Arizona Highways magazine. It was a rendezvous point for me and Jim on the front end of a week’s hunting and while I waited at camp for Jim to show up, along came a car with two men and a fine-looking woman, turning up a road right in front of my vista. They could see me as plain as day and the lady even waved and smiled, which caused my heart to flutter like a head-shot quail. The sun was easing down, a winter light blushing across the oaks and the granite in hues that would have knocked Caravaggio to his knees in deference to the true master of light.

Before long, I heard voices and as I smoked my cigar and drank my afternoon beer and watched the light show, I saw movement from atop the rocks perhaps seventy-five yards away. I grabbed binoculars for a closer view. One fella had a camera. The other had a light reflector screen. The lady was stretched out on the granite wearing nothing but a smile and striking any number of poses at the request of the camera man. The light took on an otherworldly quality. This continued until well after Jim showed up and asked to share my optics. It was a hell of a quail cover.

Scaled Quail

Another resident of this corner of the world and north into southeastern Colorado and the Oklahoma panhandle is another trickster and trackster most commonly called scaled quail, but I like another moniker better: cottontop, no explanation needed.

It was while chasing cottontops across the mesquite grasslands that my pal Greg and I discovered a glorious cut of meat called a FlankenSteak in a Spanish-only-speaking grocery in the shadow of the border fence that separates Douglas, Arizona, from Agua Prieta, Sonora. It was an unrecognizable cut of meat that was as orange as a hunting vest for all the chilies and peppers that made up the rub.

That night after shooting a half dozen cottontops each—the big covey will flush wild and run, but if you can break it up, the pairs, trios and singles will hold for a pointing dog—we grilled the FlankenSteak. Grilled to medium rare over oak coals, that neck meat was better than the best ribeye I’ve ever eaten. The next morning, we woke to a half-inch of frost on our bags by the still-warm campfire.

California Quail

Another of the running quail is the California which has been successfully transplanted into places like southwestern Idaho. Native to the left-hand coast and just into Nevada, it’s a dandy little burst of feather that helped me salvage what might otherwise have been a chukar hunt ruined by the blizzard of the century.

Alone, with no cell phone yet invented, I camped in the middle of a Sierra-Nevada blizzard that dumped three feet of snow on nearby Reno over forty -eight hours one December. Out in the camper, the heater quit and the water froze up and the bird dogs and I snuggled against one another for survival. At least the stove and oven still worked.

There was no climbing to chukar cliff country but I had whisky and dog food and elk burger and a good book, so we settled into it and waited it out. After two days, the dogs and I were cabin-fevered, so I post-holed in the blowing snow out of camp down a sagebrush draw, following the drift of bird dog on an east wind. Up went a covey of quail not one hundred yards from camp and the shotgun barked and barked again.

Our team—two setters and a young dumb human—spent the next few days hitting a half dozen coveys lightly, never taking more than a couple birds for dinner, plucked and roasted with stuffing and dribbled with bacon drippings. The snow eventually melted enough to get into chukar country and eventually out. Thriving in a big time weather event is one of life’s ecstasies, a dose of the now and the real to ensure one that hard living is the essence of being alive.

Mountain Quail

We were on another California quail and chukar expedition in the John Day country, digging into a fine cut of beef in a hotel restaurant adorned with the mounts of thirty-inch mule deer when the subject turned on this question: “Ever killed a mountain quail?”

The next day found us in a canyon of ponderosa pine. Above us was a rim of caprock where my host assured me chukar lived, but he pointed down along the stream as the home of mountain quail.

Having fresh legs and eager dogs, we went after the chukar. Up. I skirted beneath a lip of caprock, side-hilling and whistling in the dogs, sending them out again, repeating. Nothing. We hiked several miles, crested the rim of the canyon and saw the whole world open to us below, the splashing stream, the big yellow pines, the sliderock. We sat for a time contemplating a good hike with a good shotgun and canine pals, then dropped back toward the pickup.

We were halfway down the canyon when Sage went on point and up burst a covey of quail. I had a good going-away and dropped one, which my little setter girl retrieved and then we pushed after the covey rise. They went up once again and I scratched down another going-away. And thus ended, in that glorious setting, my accidental quail slam, each memory as glinting and brilliant and precious as a feathered gem.

Back to those Hummels...In 1950-something, my grandmother Agnes’ youngest son, my father, was a skinny young eye doctor working in an Army hospital in occupied Berlin when he sent home a genuine Hummel figurine for his mother.

I’m sure that little trinket brought great happiness then and years later, for it was more than a three-inch tall bit of paint and porcelain; it was a symbol, a thread between mother and son. So therein lies the thing that my grandmother and I have in common other than a quarter of my genetic code, from those cavemen of 60,000 years ago all the way to the sun-washed cliffs of my most memorable Mearns’ cover, and that thing is joy.

That’s what we collect in our lives, little pieces of it. In some it exists only in cerebral core and perhaps is translated to written word or rock carving and in others it is memorialized with a memento to put on a shelf.

It carries on through generations, from the dentist in Fort Worth I never knew who turned my best friend into a setter man who turned me into a setter man who turned Greg and a half dozen others into setter men. The frenetic pursuit of joy is at the core of the gathering game, in both feathers and life.

Tom Reed is the author of several books including Give Me Mountains For My Horses. He lives with his family and setters in Montana.

Tanner Swank is an artist and Quail Forever Farm Bill Biologist based in Woodward, Oklahoma

THIS STORY ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE SPRING 2020 ISSUE OF QUAIL FOREVER JOURNAL. IF YOU ENJOYED IT PLEASE CONSIDER JOINING OR RENEWING YOUR SUPPORT FOR QUAIL FOREVER BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK AND HELPING US PROTECT THESE CRITICAL AREAS AND THESE CHERISHED TRADITIONS. JOIN TODAY AND YOU'LL RECEIVE A FREE $25 GIFT CARD TO BASS PRO SHOPS OR CABELA'S!